8

8

1802年的6月,洪堡爬上了当时公认的世界最高的山峰——海拔6267米的秘鲁钦博拉索火山。他的报告这样写道:“我们不断攀越云层。多处山脊不超过8—10英寸宽。在我们的左方是冰雪覆盖的悬崖,它的表层结了冰,玻璃般闪闪发亮。我们的右方则是可怕的深渊,在800至1000英尺的深处,有许多突出的巨石。”即便是危险重重,洪堡仍对多数人忽略的东西作了细致的观察:“在海拔16920英尺高的雪线上,我们看到了一些长在石头上的苔藓,我们最后一次见到青苔则是比这个高度低2600英尺的地方。在15000英尺的高处,庞普兰德(洪堡的旅伴)捕捉了一只蝴蝶,而一只苍蝇出现在比此处高出1600英尺的地方……”

In June 1802, Humboldt climbed up what was then thought to be the highest mountain in the world, the volcanic peak of Mount Chimborazo in Peru, 6,267 metres above sea level. 'We were constantly climbing through clouds,' he reported. 'In many places, the ridge was not wider than eight or ten inches. To our left was a precipice of snow whose frozen crust glistened like glass. On the right lay a fearful abyss, from 800 to 1,000 feet deep, huge masses of rocks projecting from it.' Despite the danger, Humboldt found time to spot elements that would have passed most mortals by: 'A few rock lichens were seen above the snow lines, at a height of 16,920 feet. The last green moss we noticed about 2,600 feet lower down. A butterfly was captured by M. Bonpland [his travelling companion] at a height of 15,000 feet and a fly was seen 1,600 feet higher … '

一个人为何会对苍蝇出现的确切高度产生兴趣?他又为何会关注长在10英寸宽的火山脊上的一片青苔?这份好奇心并非突然产生的;洪堡对这些事物的关注已久有时日了。苍蝇和青苔之所以吸引他是因为它们关系到先前出现的更重大、并且对于外行人来说更能理解的问题。

How does a person come to be interested in the exact height at which he sees a fly? How does he begin to care about a piece of moss growing on a volcanic ridge ten inches wide? In Humboldt's case, such curiosity was far from spontaneous; his concern had a long history. The fly and the moss attracted his attention because they were related to prior, larger and-to the layman-more understandable questions.

好奇心像是由一连串向外拓展、并且有时延伸到深远处的小问题所引起,好奇的轴心就是几个没什么来由的大问题。我们小时候会问:“为什么有善与恶?”“大自然如何运作?”“我为何是我这个个体?”如果环境和个人性情的发展得以配合,我们在成年的岁月中会继续探讨这些问题。人们的好奇心会涵盖更广阔的天地,最后到达什么都觉得新鲜,有趣的阶段。那些混沌的大问题便引出了更细微和深奥的问题。于是我们开始关注生存在山坡上的苍蝇,或者16世纪宫殿中的一幅壁画。我们也开始关心一位早已不复存在的伊比利亚君王的外交政策,或者女人在30年战争 [15] 中扮演的角色。

Curiosity might be pictured as being made up of chains of small questions extending outwards, sometimes over huge distances, from a central hub composed of a few blunt, large questions. In childhood we ask: 'Why is there good and evil?' 'How does nature work?' 'Why am I me?' If circumstances and temperament allow, we then build on these questions during adulthood, our curiosity encompassing more and more of the world until, at some point, we may reach that elusive stage where we are bored by nothing. The blunt large questions become connected to smaller, apparently esoteric ones. We end up wondering about flies on the sides of mountains or about a particular fresco on the wall of a sixteenth-century palace. We start to care about the foreign policy of a long-dead Iberian monarch or about the role of peat in the Thirty Years War.

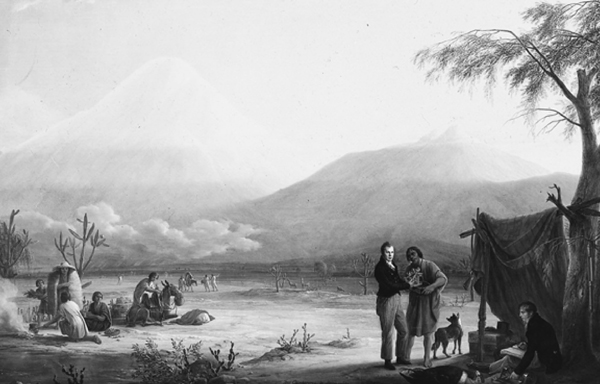

弗里德里希·乔治·魏奇:《钦博拉索山下的洪堡与庞普兰德》,1810年

洪堡早在童年时就想到一系列问题,这些问题导致他在1802年的6月中,对钦博拉索山10英尺宽的山脊上的一只苍蝇产生好奇心。他7岁那年从柏林老家到德国别处拜访亲戚时就问自己:“为什么同一类植物不能在所有的地方生长?”为什么长在柏林周围的树不出现在巴伐利亚?反之也一样。他的好奇心受到他人的鼓励。他得到了大量关于自然界的书籍、一个显微镜以及数位了解植物学的家教老师的指导。他成了家中的“小化学家”,母亲更在书斋的墙上贴上了他完成的植物画作。当洪堡前往南美洲的时候,他已经尝试找出定律,以解释气候和地理环境如何影响动植物。他7岁时对事物所产生的质疑感并未减弱,只是这份好奇心以更复杂的问题形式体现出来,例如:“如果北面是曝露面,那么蕨类植物是否会受影响?”、“一棵棕榈树能够生长的海拔极限有多高?”

The chain of questions which led Humboldt to his curiosity about a fly on the ten-inch-wide ledge of Mount Chimborazo in June 1802 had begun as far back as his seventh year, when, as a boy living in Berlin, he had visited relatives in another part of Germany and asked himself: 'Why don't the same things grow everywhere?' Why were there trees near Berlin that did not grow in Bavaria and vice versa? His curiosity was encouraged by others. He was given a library of books about nature, a microscope and tutors who understood botany. He became known as 'the little chemist' in the family and his mother hung his drawings of plants on her study wall. By the time he set out for South America, Humboldt was attempting to formulate laws about how flora and fauna were shaped by climate and geography. His seven-year-old's sense of inquiry was still alive within him, but it was now articulated through more sophisticated questions such as, 'Are ferns affected by northern exposure?' and 'Up to what height will a palm tree survive?'

洪堡在抵达钦博拉索山脚的营地后,先洗了脚、午睡了一会儿,就几乎立刻开始动笔撰写《有关地理和植物的论述》。他在文中界定了植物在不同高度和温度下的分布情况。他把海拔高度分为6个区。从海平面至海拔3000英尺的高度,生长的植物有棕榈树和香蕉树。蕨类植物生长至海拔4900英尺的高度,而橡树则能生长至9200英尺的高度。接着是常青灌木(如胡椒木和鼠刺),而最高的两个区为高山区:从海拔10150至12600英尺的高度,香草得以生长,而海拔12600至14200英尺的高处则能见到高山草和苔藓。他还兴奋地写道,苍蝇不太可能出现在海拔16600英尺的高度以上。

On reaching the base camp below Mount Chimborazo, Humboldt washed his feet, had a short siesta and almost immediately began writing his Essai sur la géographie des plantes- in which he defined the distribution of vegetation at different heights and temperatures. He stated that there were six altitude zones. From sea level to 3,000 feet approximately, palms and pisang plants grew. Up to 4,900 feet, there were ferns and up to 9,200 feet, oak trees. Then came a zone that nurtured the evergreen shrubs (Wintera, Escalloniceae ), followed on the highest levels by two alpine zones: between 10,150 and 12,600 feet, herbs grew, and between 12,600 and 14,200 feet, alpine grasses and lichens. Flies were, he wrote excitedly, unlikely to be found above 16,600 feet.